Since September 2020, Anna-Maria Nabirye has been working with Cement Fields as part of our Jerwood WB Artist Attachments, a bespoke development programme providing paid time and support for three early-career artists.

She sat down with artist and curator Nephertiti Oboshie Schandorf to discuss her work and influences, and the importance of prioritising love and care in creative practice.

Nephertiti Oboshie Schandorf: How you doing this morning?

Anna-Maria Nabirye: I’m good. I feel very aware of being Black this morning, the labour of being Black. There’s been a few little shenanigans that have been going around in my town with white-led organisations, and it’s very tiring. Even if you decide to not engage with it, you still spend a lot of time deciding not to engage with it, either way it takes up a lot of brain and energy space.

NOS: Yeah, I feel you. It’s happening a lot at the moment, a strange hand-wringing. Do you want to talk about what’s happening around you?

AMN: It’s lots of little things. With my project Up in Arms, we are looking for a local stage manager. So I did a call out and said it would be really great if you had an anti-racist practice or understanding as part of your stage management practice. And then mainly I got these aggressive applications back: ‘I’m a stage manager, I’ve been doing this for blah, blah, blah years… I don’t understand what you mean by… I go where the work is… I’m a human and connect with humans…’ And I’m like, if you don’t understand anti-racism you could just Google it.

NOS: To ask for decency also involves anti-racist practices. And other things, because racism is not the only exclusion that people are facing. It’s also things like ableism, or understanding that people have different life experiences. If you want to achieve something together, you’ve got to find your common ground.

AMN: I think before I’d have sent an email back, and I’d have expended energy on it. But now I don’t respond. Delete. Done.

NOS: Yeah, that’s a protective thing. You’re not someone’s learning experience. You’ve got things that you want to create, right? You’re an artist because you’re rewarded and fulfilled and nurtured and developed by creation.

AMN: Yes, creation and curiosity. That’s what’s so interesting about all of these fear responses: it’s really shutting down curiosity. When people use words or phrases that I don’t understand, or terminologies I find challenging, I’m curious. I want to find out why. Why does that make me feel awkward or defensive?

NOS: It’s such a personal thing, it’s informed by our tolerances. Some people recognise that they’re defensive, and yet they’re still defensive. And you have to ask them, ‘What did you hear being said in this question?’ But how much of that do you carry? You have a big sister energy…

AMN: I am such a little sister, but it’s funny that I have big sister energy. I like that!

NOS: It’s a search for justice. That’s what I consider big sister energy – they have all the pressure put on them to be perfect. And so if they see something wrong with the world, they feel it’s their responsibility to fix it.

AMN: I’m really trying to let go of that. Which is why recently I’ve been wanting to work in this joyful space, centring Black women in the work. Asking, ‘How do I continue the fight for justice but in a much more healing and community-led way?’

NOS: If you want that space, and it’s not there, you’ve got to make it. I’ve been thinking about your video, Gestational Diabetes: One Prick at a Time. How did you get into that subject?

AMN: I started an enquiry with Jess Mabel Jones about motherhood, as we were at a stage in our lives where all of a sudden people – from vague acquaintances to shop assistants, colleagues etc – were asking if we had children or when we were planning to – it was insane. It’s like: ‘Don’t get pregnant! … Don’t get pregnant! … Don’t get pregnant! … Where’s your baby? … Where’s your baby? … Where’s your baby?!’ So we held a series of workshops and created a zine for The Albany Theatre, gathering lots of different people who were mothers, weren’t mothers, who couldn’t be mothers, who chose not to be mothers, who mothered without birthing a child – a very diverse group of experiences. Then curator and arts producer Ruth Guard shared the call out for a proposal to make a work that centred the experiences of women with Gestational Diabetes for a King’s College research fellow. We were really excited about continuing that enquiry, thinking about the intersection of women’s bodies, the medical world and motherhood. It was also made in lockdown, which was really tricky. How do you create relationships of trust with people you’ve never met? That was what drew us to the subject, wanting to centre voices that hadn’t been heard.

NOS: There were definitely parts of it that are difficult to hear. You could get this disease through pregnancy that could put you and your pregnancy at risk. How did you find the women?

AMN: We found them through working with Gestational Diabetes UK. They span the whole country, so we got to work with people in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, in a way that we wouldn’t have if we were meeting people in real space. I love the journeys to collaborations. When I was listening to your piece, Sospiro, I was really interested in your collaboration. How did that come about?

NOS: Sospiro was about breath and included opera singers, Julia Daramy-Williams and Jaqueline Yu, and a violinist, Blaize Henry. It’s a very gentle and communal performance, breathing with people. This was before lockdown, probably one of the last times you could have 50 people in a room together, breathing at volume. I found it very, very beautiful. I’ve worked with Blaize before and I just love the working process. Violinists are like athletes: they get injuries, there’s so little room for error. To find someone who’s classically trained, who’s also relaxed enough to improvise is so rare. It was also a really lovely space to have diasporic talent, and the focus was on their talent and their skills, not their heritage. I want 14 year olds to see this and think, ‘Oh, I could do that.’

AMN: I really love the idea of tuning up. Something that I come across a lot in teaching theatre is that students get really flustered when they’re speaking and they haven’t quite got their point together. They’re like, ‘Oh, I’m just talking in draft’ – that’s a phrase I’ve heard a lot. And I’m like, well, aren’t we all? With classical music everything seems so precise, even the physical language of how people walk on stage.

NOS: With Sospiro, it was a very big, quiet, incredibly reverent room – it was very cold. I’d asked for hot jasmine tea and blankets, and the chef made rose and pistachio cookies. There’s a hospitality in it, right? That’s something that’s really important for my working class, Ghanaian upbringing: if people come to your house, you show them love when they come in. I hadn’t realised this was a curatorial concept. But doing my MA I was introduced to a curator called Suely Rolnik, and she was like: curatorial care.

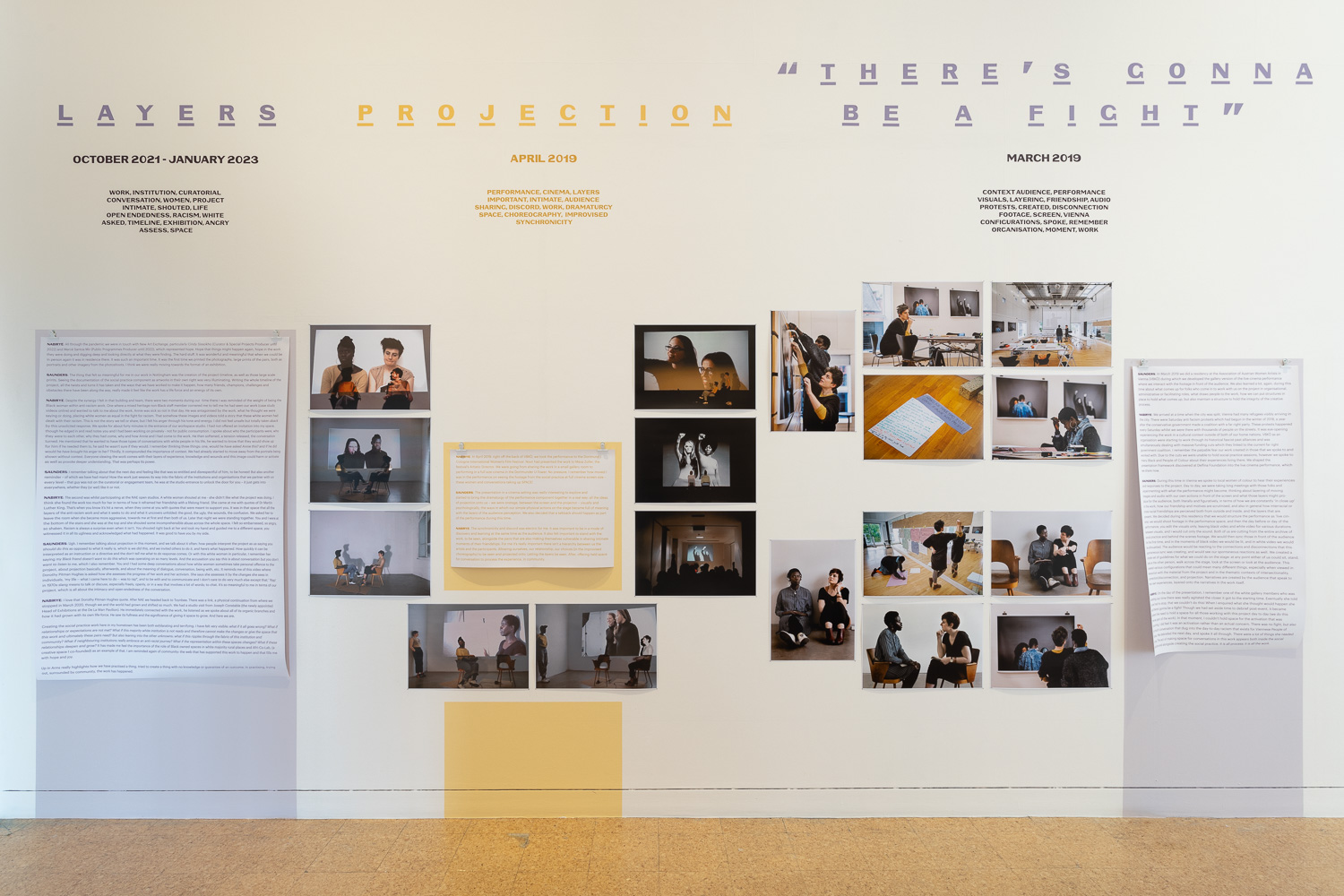

AMN: I really resonate with that: in my visual arts work, it’s important to me to imagine what people might need. With Up in Arms we’ve created another space upstairs to decompress, hang out, to talk. There’s a lot in the work that could feel very personal or activating. So the room upstairs has sofas, throws, cushions, books, soft lighting. If I had my way, I’d have free tea up there all the time. For me, it feels as much a part of the art as the photography or the film. We also had lots of different book titles by Black authors in the bookshop: Toni Morrison, Reni Eddo-Lodge, Audre Lorde, Octavia Butler. It feels so important: how people arrive at the work, how people are held during the work and how people are held on the way out.

NOS: I’ve seen it in some of your work. In Black Joy Matters the audio really got me: chatting shit with one’s friends, the dancing and the silliness and the acknowledgement of weariness. Physiologically fortifying.

AMN: My dream is to go around the country speaking to Black folks about what makes them joyful, and what makes them laugh. To be filled with that, as opposed to being filled with trauma, which is the other space that is often given to me to occupy. With each of those interviews, I tried hard to create an act of love: I made them brunch, or we had cocktails, or a nice meal, or we went for a walk.

NOS: There needs to be lightness. There is a lot around trauma in the arts. And it’s great that people can speak to it. But maybe people don’t want to constantly discuss their trauma in a forum. Not everything has to be so serious. The water’s dirty, there’s no clean air, there’s bird flu, there aren’t any cucumbers in the supermarkets. There are terrible things happening in the world, but what’s brought people through is the bonds that we can form with each other. I had a discussion group and one of the things that came up was around rest in the institution and the cycles of burnout. When we started our conversation today, you had a weight on you. That was the big sister energy, there was some stuff that you had to fix. And you’ve got so much that you are doing that is more deserving of your energy.

AMN: I really like that as we’re just about to finish we’re finding this place of love as a practice, and care as a curatorial process.

NOS: Absolutely. Go find your joy.

This conversation took place in March 2023. Up In Arms has closed as of May 2023, however Anna-Maria is currently writing a book about the project with co-creator Annie Saunders and thinking about where the work will travel next.

Anna-Maria is also currently working with ArtsAdmin to re-develop her work The Funnest Room In The House, and is keen to speak with people interested in collaborating on the next iteration of the project. The work, developed as part of the Jerwood WB Artist Attachment, was originally commissioned for Whitstable Biennale 2022, but tragically was lost to a fire in the venue two weeks before the festival.

Find out more about Anna-Maria’s work at www.annamarianabirye.com.