An Amphibian Vision: William Fowler

Stan Brakhage’s 1963 poetic essay Metaphors of Vision is often used to reframe the potential of cinema and to illustrate what experimental film, as a codified discipline, might be trying to do. Stripping away preconceived ideas about meaning and identification, it asks readers to simultaneously see the world with unblinkered eyes and to put faith in celluloid as a restorative vessel. It is an effective, evocative text for leading people to experience artist’s film without judging it according to criteria developed through film reviews and thinking that invariably offers critique according to more literary and theatrical traditions.

Imagine an eye unruled by man-made laws of perspective, an eye unprejudiced by compositional logic, an eye which does not respond to the name of everything but which must know each object encountered in life through an adventure of perception. How many colors are there in a field of grass to the crawling baby unaware of “green”? How many rainbows can light create for the untutored eye? How aware of variations in heat waves can the eye be? Imagine a world alive with incomprehensible objects and shimmering with an endless variety of movement and innumerable gradations of color. Imagine a world before “the beginning was the word”. – Stan Brakhage

As well as describing a form of looking, it suggests an embodiment of that vision, asking us to cast our minds back to what it might have been like as a newborn child when our consciousness was still forming. It was this that came to mind when discussing the research and thoughts behind Phil Coy’s forthcoming film, Grit, which has evolved from his research into the phenomenon of coastal darkening. He speaks of an amphibian vision, placing his research within a larger history of artist’s or experimental film, while asking questions about what it might mean to re-examine our abusive relationship to the sea and its complex histories.

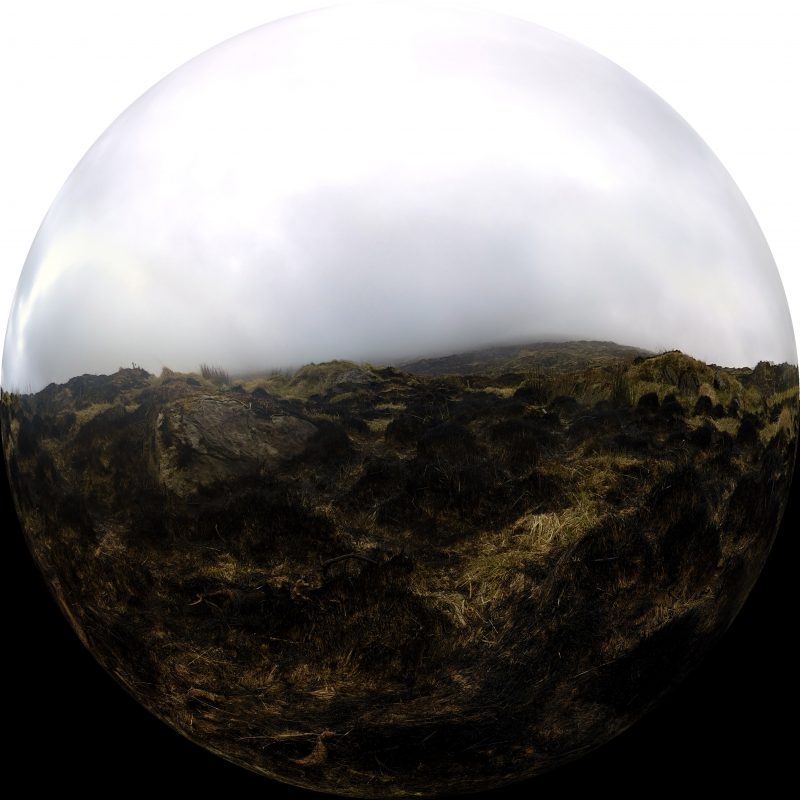

An amphibian vision, Grit intends to use the fish-eye as a structural device and metaphor that holds a lens to a slowly unfolding metanarrative: here the fish eye is revealed, through its role in evolution, as the source of all vision on earth; and through its ability to regenerate, offering a potential cure for humanity’s diseased vision of the future. – Phil Coy

The appearance of an eye as it emerges from the sea, crossing from one world to the next, evokes suggestions of transformation and translation, recalling the moment our biological ancestors, tiring of the water, crawled out to see the grass without any conception of the colour green, as Brakhage has it. The birth narrative of breaking water gives voice to the sea and its creatures – and it also extends further. Coy intends to look at the use of the eye of the zebrafish as a means to augment and repair human vision, to fuse perspectives in an almost cyborg fashion. Paradoxically, the results and affect are more pre- than post-human, and as much about seeing differently, as it is to see better.

A ‘diseased vision’ is one of rigid codification, one incapable of seeing different possibilities or different futures, and also versions of the past. Phil Coy previously explored the overwhelming force and logic-breaking power of the sea in Wordland (2008) – again, as Brakhage has it above, imagining a world before the ‘beginning was the word’ – and Avoiding Green (2017), which both unpicked and wove the material and oral history of knitting and the gansey, the fisherman’s jersey. Each film offers a reframing of histories and refusals of the strict, rigid delineations of form.

Phil Coy, Wordland (trailer), 2008. Watch in full here →

The intention of Grit, as the third in a trilogy, is to consider, in Phil Coy’s words, ‘our relationships with the coast, each drawing upon the territorial relationships between the sea and those who choose to live and work with it.’ Making associative connections between studies in the evolution of the eye, retinal regeneration and the phenomena of coastal darkening, it will combine research from UCL’s Institute of Ophthalmology and University of Hull’s Institute of Estuarine and Coastal Studies. It will include interviews and conversations with ophthalmologists, marine biologists, architects, builders, seafarers, civil engineers, climate scientists and those affected inshore. As Coy describes it: ‘Emerging from the increasingly murky depths of the sea and shot as if through the saline eye of a fish, Grit unpicks a little-known phenomena of a steady decline in water clarity, and a literal darkening of waters around the world’s coastlines over the last 50 years.’

For Grit, Coy proposes the use of the fish-eye lens as camera, warping vision and evoking the use of an eye designed for other purposes: the fish’s eye reading depth and negotiating the refractory qualities of water. Easy Rider (1969) famously used such a lens when filming the rebellious lead characters’ acid-trip horror, bending the light and suggesting that Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda’s characters were at odds with the world and ‘like fish out of water’.

Giving voice to the sea is a contested or problematic challenge that several creative artists have responded to. David Gatten avoided the concept of traditional visualisation in his series What The Seas Said (1997, 2007). Submerging unspooled film stock inside a crab trap underwater in the Atlantic Ocean off the North Carolina coast, he allowed the abrasive effect of the sea and the crab trap to create the image in collaboration with the chemical, physical make-up of the film strip. Stan Brakhage made his Commingled Containers in 1996, which utilised an anamorphic lens to move from pulsing forms of underwater light to the whites of water turbulence, finally ending on a surface shot like the visionary emergence of an amphibian or sea monster or a bobbing message in a bottle rising with a secret missive.

But the attempt to give visual form to the ocean in the UK has historically been tied up with expressions of power, implicitly touching on very specific ideas about nation, and even Empire. While an amphibian vision looks from the sea to the land, this contrasts with the historical tendency with film and the ocean.

The 1896 film Rough Sea at Dover was filmed from a tripod on the seafront, the camera peering out at waves smashing against Admiralty Pier. The point was to capture violent movement, as a way of powerfully illustrating the possibilities of the newly emerging cinematograph machine. One of the very first films made in the UK, it was exceptionally well received and it received a powerfully enthusiastic response at the Koster and Bial’s Music Hall over in New York when it crossed the Atlantic in April 1896. Several films played that evening but the New York Evening Mail and Daily Express remarked that ‘this was by the far best view shown, and had to be repeated many times’.

Tightly framing the breaking waves also had the effect of exaggerating the power of the sea. Typically, the sea is rougher and more energised when it enters a deep harbour, such as the one at Admiralty Pier, as it meets physical structures and changing depths. Thirty, forty feet away, it might be relatively still. The use of film expressed more of the sea’s state than would have been apparent to anyone present at the time the film was shot; technology reshaped perception of powerful natural phenomena. This was not insignificant when, at this time even in an island nation such as the UK mainland, trains to the seaside typically catered to the monied classes. Many people encountering Rough Sea at Dover, in a music hall or in a circus far from the coast, might conceivably never have seen the sea before.

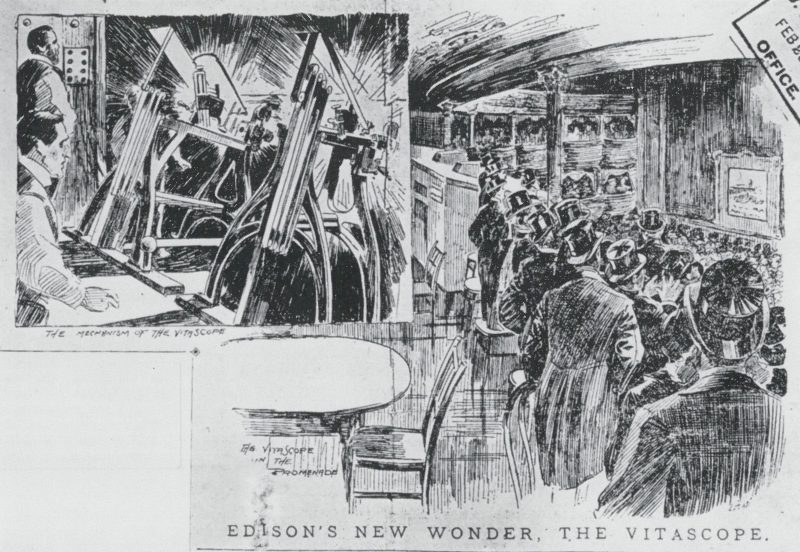

Multiple rough seas films were made in the wake of Rough Sea at Dover, at least 30 in the UK between 1895 and 1904. Edison’s company even gleaned their own when visiting the UK to film Edward VII’s coronation, probably having seen or heard about the screening at Costal Music Hall, New York. Waves at Dover, England (1902) was available as a discrete film in the larger series. This meant that a booker could hire just that individual film, should they wish; it more broadly suggested that there was something symbolically and particularly British and Imperial about this type of film and its location.

Only two years later, crowds at the Palace Theatre in London roared with jingoistic fervour when they saw Lord Kitchener arrive first at Calais and then at the very same Admiralty Pier at Dover after victory in the Sudan in 1898. Dover has its ‘white cliff’ mythologies but it also marks the closest crossing between England and France, just 21 miles, and a shallow one at 216 feet at its deepest. Three-times Prime Minister William Gladstone referred to this particular stretch of water between Dover and Calais as the ‘wide dispensation of the Province’ and ‘that streak of silver sea’ as if it were imbued with some holy, nationalistic, baptismal power.

But rough sea films were shot on multiple coastlines around the UK. The stationary position of the camera that framed the sea from the perspective of the land had a precedent in picture postcards, rough seas being exceptionally popular here (see the artworks of Susan Hiller, an artist who collected hundreds of these), and in painting. This imaging was thought to evoke the curative possibilities of the sight of the sea and suggest the feeling of its force upon the body. There was thought to be something utopian and timeless about the imagery, even if it played with notions of death and danger too. Considerable lives had been lost in the Napoleonic Wars and in the late-nineteenth century, with the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, European power was in the throes of being remapped. And still, the films offered a respite. Such views were not neutral or devoid of the signs of their times. The use of the technology was ideological but the films also invariably betrayed changes in the landscape. Waves Breaking on a Pier (1896) shows Brighton’s Palace Pier being constructed, as if Britain’s ideology regarding the sea needed to be further stretched out from the land in another physical structure after the previous pier had been destroyed in a storm, extending the country’s dominion and its relationship with the sea, probably in the name of the developing field of tourism.

This may come across as a series of over-readings but we know from recent history that British isolationism and sense of exceptionalism persists to this day and into this age of Brexit. In the late-nineteenth century talk stirred about a bridge being built between Dover and Calais; it was, as one might expect, extremely divisive. There was an acute sensitivity to questions of nation and its indirect manifestations, as ever.

It is notable that the most famous French equivalent to the rough sea film in early cinema is Barque sortant du port, a film centred on a narrative of the boat’s passengers leaving their tearful loved ones behind for who knows where. British examples, by way of contrast, centred on the purely sensational effects of the sea and its image. No actors are required; the sea is not the backdrop, it is the star, even in the case of films shot on a boat out at sea. Waves captured from this vantage point reduce the sensation of movement as the boat negotiates the swells of the sea with the result being more disorientating than violent and confrontational. Still, the sea is presented as a separate, threatening entity.

As well as being used to communicate symbolically nationalistic zeal, rough seas were also part of a larger colonial, museum project. Demonstrating the nation’s strength was attached to a powerful endeavour of museum practice; plundering material culture, people, animal trophies and precious metals to accumulate wealth to exhibit and enforce the small country’s dominion over the planet and its people as articulated through the Great Exhibition of 1851. Often framed as a godly, civilising force, Empire was actually more about assuming all power over everything, pushing God to one side. Appearing to snare the sea, the very force that the creator had used to lay waste to the sinful in the story of Noah and the flood, was a highly symbolic collecting and ‘museum-ing’ act, and a form of propaganda. The ‘film as museum cabinet’, which captured indexical photographic manifestations of movement such as had never been seen before, was portable and reproducible.

At once intoxicated by the viscera of rough water, these undeniably spectacular early cinema films were also predicated on distance, and the landlubbers’ fetishisation of the romance of the sea and the world further afield. It is this distance that has allowed us to ignore the environmental effects of sea pollution on an astronomical scale but also to shore up the diverse boundary points of nation while engendering a resistance to refugees and a blindness to the (sea) atrocity history of black slavery. Hydra Decapita (2010) by the Otolith Group considers the Afro-futurist reimagining of the repercussions of slaves cast overboard between Jamaica and Liverpool from the ship The Zong in 1781. Louis Henderon’s The Sea is History (2016), which re-envisages European colonial history and the sea through an adaptation of a poem by Derek Walcott. These two moving-image works present attempts to recuperate and place a lens on these obscured histories in the wake of, among others, Paul Gilroy’s 1993 book The Black Atlantic. Dover remains a contested site of over-mediation and concern regarding the so-called threat of a tiny number of people who brave the perils of the sea in the hope of refuge in the UK. The status of these desperate people remains charged and divisive; for some appearing to evoke questions of Empire, sovereignty and a rigidity of borders as if to shore up a place that has seen countless numbers of people come and go in all manner of circumstances over the last millennia and indeed further back into time. In reality, these refugees risk life and death.

All these thoughts set the stakes very high, higher than can be easily or entirely responded to or redressed. But this symbolic mode of visioning can potentially be explored and unpicked. Phil Coy’s proposal and research, which has its own particular focus, offers an alternative to the Terra firma bias of early cinema and all its attendant symbolism. And it builds on his earlier visioning projects, notably Substance (2019), which partly fused interior and exterior landscapes through the use of a hemispheric 360-degree interactive VR installation, complicating landscape visualisation and how it is received.

In this new context and for this new work, ‘an amphibian vision’ presents a resetting of the eye and of historic ways of looking, one that dethrones a certain form of human power. How do and can we see and more clearly manifest all these and other sunken histories?

Phil Coy’s Grit focuses on certain aspects: the framing and concept of vision and what it reveals, yet simultaneously obscures, as we move between places, spaces and contexts. Coy proposes another type of symbolic vision to that of earlier cinematic models, with a different sense of implicit power encoded within it. As a metaphor of vision, the light shining both on and from the land is turned down and the darkness in and of the waters is turned up.

—

Acknowledgement: On top of the writings and films already detailed, I would like to mention: the books An Oceanic Feeling: Cinema and the Sea by Erika Balsom and Cinema’s Military Industrial Complex edited by Haidee Wasson and Lee Grieveson; the exhibition by Filipa César & Louis Henderson, Op-Film: An Archaeology of Optics; and the films Territories by Isaac Julien, Exile Exotic by Sasha Litvintseva and several works by William Raban and Chris Welsby (made individually and together), which were all in my mind or contributed to my thinking, however obliquely, as I wrote this piece.

Afterword: Phil Coy

Norfolk is a low-set watery chunk of land that resembles a bare fist sticking out into the English Channel. My father lived on one of its promontory knuckles, in a 1940s prefab bungalow, set behind some low dunes in a loose grid of untarmacked roads. The small huddle of buildings in this former holiday resort were an unsettling reminder of the once much larger village of Eccles-next-the-sea, which had, since a great storm in 1507, become Eccles-in-the-sea. Following another devastating flood of 1953, the seaward side of the dunes had been lined with concrete sea defenses. Flickering into view, I can still see my father striking a comedic pose on the shoreline, making stoic assertions of ‘a lost village’ out to sea. He, like most of its denizens and visitors, knew the place for what it once was rather than what it had become.

The blame for this strange abstraction of memory and place, must go to the long-submerged St Mary’s church tower, which had for hundreds of years, stood improbably on the beach. A favoured subject of the Norwich School of painters and early photographers, the resulting watercolour paintings, etchings and photographs can still be found on tourist postcards, touting that peculiar melancholy of the reproduced reproduction. This afterimage on the landscape, burnt onto the collective retina, continues to raise this crumbling edifice, assuring its continued dominion over the still receding coastline.

My relationship to North Norfolk was entwined with the experience of coming to it from London. This was heightened by my father condensing London into the clutch of buildings around Liverpool Street and the City, not an actual place for him, or somewhere I lived, but rather the idea of a place fed by totemic images of glass and steel. Before living in London, I would occasionally pass through its core, from station to station, glimpsing a slow metamorphosis of blackened brickwork façades mutating into shiny linear outgrowths. These snatched views seemed to tally with the same technicolor images of a city I had absorbed from watching films with my father as a child. Living in London as an adult, the buildings’ gargantuan proportions served more to infantilise me, magnifying the implausibility of my being there. Those celluloid images from childhood, where cities were imbued with an Oz-like aura, quickly dispersed in the grey fumes of the street. Taking their place was an architecture that resolved with the simple clarity of any product. The buildings had the appearance of being administrated by a particularly mundane algorithm, whose sole purpose was to generate materials and employment in exact proportion to the density of immaterial labour that could be amassed. Lessons in perspective drawing and Euclidian geometry had melded with the efficiency of scalable vector graphics, to form a congregation of large and improbable developments.

For my part, I joined a captive audience living in the East End, bound to look up anxiously at this emerging virtual reality. From that vantage point, it was the building sites that commanded the stage. Perpetually accruing elevations displayed an animation of constructions in process. Their slow dance, one of lattice towers and concrete cores, would slowly fade as the latent energy of work and materials receded, and the outer skins of the architects’ plans took form. When the set was cleared away, and the labour of its players gone, our spectatorship became one of transients and passers-by, left to perform one last physical stretch – that of our necks, raising our eyes upwards to gaze on the now intimidating levels of triumphant largess.

With this as a backdrop, Liverpool Street station, where the trip began, had resolved into an architectural point break, its engorged geometries as intrinsic to my journey as the sagging horizons of my destination. The city’s vertical massing seemed to be rising in proportion to Norfolk’s ebbing – a land of dark fertility and sleepy waterways slowly bleeding into the sea. Prompted by a motley lineage of retired greyhounds, days at my fathers were punctuated with regular walks along this collapsing coastline. Watching in slow time, as houses edged closer to the sea, helped level my battles with London’s endless rising rent cycles. Witnessing the power ascribed to property, the house and all its contents fall away, was consolatory, and the need to capture that process on film, became a therapeutic endeavor.

Working with City Projects, we hired equipment and scheduled filming to start in late November 2007, when a surprise call from my father, told us that the spring tides – those with the biggest difference between high and low water – had arrived early. This event forced the first day of filming and, heading up to Norfolk, I captured the morning-after the deluge, where houses had been flooded and destroyed in the nearby village of Walcott. Revisits to Norfolk that winter allowed for successive interviews with those affected. With the help of the artist Frances Kearney, who had grown up and lived in Cley-next-the-sea, I was able to film many of the survivors of the 1953 floods. Unexpectedly, the collision of recent and distant memories, of separate floods in different villages, prompted a slippage between memory and language.

During the edit, and while looking through films documenting the 1953 floods in the East Anglian Film Archives, I first met William Fowler, and learnt about his research into early British rough sea films. It was a real surprise to find out we shared an interest in this slender classification of archive film and a delight to learn how intimately connected these films had been to the birth of cinema in this country. His insights strengthened my attention to the blurred lines between land and sea and to where the arbitrary confines of land and property give way to lived experience. Like those first witnesses of early rough sea films that William describes, entranced at screenings, I too became bound to images of the sea, and the want to leer into successive waves of aqueous materials.

This same compulsion has led to the making of Grit. Pulled by the undercurrents of Wordland (2008) and the subsequent film in this series Avoiding Green (2017). With that film, I looked at relationships between knitting and the sea, interested in exploring the entrenched tradition of men working at sea and women supporting their endeavour ashore, wanting to hear more from their different perspectives. Filming along the East coast of Yorkshire, I used a technique of volumetric filming, colliding the binary structure of the digital image, with the physical on/off nature of knitting.

The circuitous route to this work opened up further during a talk about Avoiding Green with the marine biologist Magnus Johnson at Ferens Art Gallery in 2017. Magnus made me aware, for the first time of ‘Coastal Darkening’. The eponymous study reveals how the effects of human activity, both inland and at sea have decreased water clarity around the world’s coasts, which has in turn had an increasingly detrimental effect on marine habitats. Those two words ‘Coastal’ and ‘Darkening’ stayed with me, becoming a Baedeker for this project during the political and environmental upheaval of the last four years. In tracing the affects that led to this receding marine vision I met with one of the study’s authors Rodney Forster and visited the sites of its industrial causes; the farms, quarries and aggregate companies whose processes generate turbidity in the water. With the optics of the fish-eye coming to the fore, I also met with Dr Mariya Moosajee, whose research at Moorefields Eye hospital has helped develop gene therapies from the regenerative optic cells of Zebra fish to treat macular degeneration in her patients. Grit makes no claim on these significant studies other than to shine a light through them. The process that leads to the work is one of aggregation and collision.

—

William Fowler is Curator of Artists’ Moving Image at the BFI National Archive where he acquires, restores and curates films. His projects have included Queer Pagan Punk: Derek Jarman, the biggest ever UK retrospective of Jarman’s films and This Is Now: Film and Video After Punk which toured internationally in collaboration with artist moving image agency LUX. He is also a writer and his co-authored book The Bodies Beneath: The Flipside of British Film and Television was published by Strange Attractor Press in 2019.

Phil Coy is an artist working across a broad range of media, collaging concepts rooted in the radical art and literature of the 20th century, with languages and architectures of contemporary global commerce. He often works with specific communities, architects, software developers, musicians and scientists to produce films, sculpture, performance and audio works. A new permanent outdoor sound sculpture Stereo Pair [two listening devices], developed from pre-radar listening devices and brutalist architecture, will be launched in 2021 at Brunel University London and a new commission for Matt’s Gallery will coincide with the launch of their new space in Nine Elms in 2021.

William Fowler’s An Amphibian Vision and Phil Coy’s Afterword are abridged texts which will be published in full in Grit and Grain [a film reader] to accompany the release of Phil’s forthcoming film Grit.