Savinder Bual is an artist fascinated with the illusory qualities of cinema and early animation. Creating works that sit between the pre-cinematic and the digital, her work explores the interplay between the moving and the still and juxtaposes tangible everyday materials with the immateriality of video.

As part of her residency with Cement Fields, Savinder spent time exploring the Isle of Sheppey, observing the place and forming ideas which will be explored further over the next two years, towards a new commission for Whitstable Biennale 2022.

I had the opportunity to visit the Isle of Sheppey which before this time was unknown to me. The warm and welcoming ‘Swampys’ as they proudly call themselves would prefer to keep it this way as they do not want their island to become another Whitstable. Still, they appreciated me visiting in stormy February at a time ‘where you get to know the community better’. Each part of this small island is distinct. On the Isle of Harty overlooking the rough waters of the Swale there is a sign. On it is written ‘Time and Tide’, Now wild and peaceful this special place has been formed by the ebb and flow of the tides.’ Sheppey is made up of clay that is literally being sculpted before your eyes. It is an island that requests us to observe.

On it there once stood an observation device that allowed the sea to draw itself. Its purpose was to measure the point where the sea touched the land at any given time. From 1830 this pioneering device recorded the movements of the tide both day and night, marking the sea levels. It consisted of a copper float that rested on the surface of the sea within a stilling well that kept the float from moving side to side. Its rise and fall was communicated through pulleys to a pencil that drew delicate lines on a huge roll of paper placed on a revolving cylinder.

As much of my work refers to early cinema and the observation of movement, the mechanics of this device and the shifting clay of the island it once stood on fascinates me.

Coming across an old fashioned seaside telescope looking out to sea at Leysdown. I was reminded of the first publicly screened film in Britain, entitled the ‘Rough Sea at Dover’. The film consisted of a fixed shot of waves crashing over a Jetty. It was intended to be viewed through a peephole device called a kinetoscope.

I excitedly placed 50p into the slot of the viewfinder to see the sea view magnified 10 times. The shutter opened and to my dismay, all I saw was condensation on the glass of the lens. I had been told that time had stood still at Leysdown. That they hadn’t spent a penny on it in 50 years. For me, there was something reassuring about this place in a world that seemed to be changing so fast.

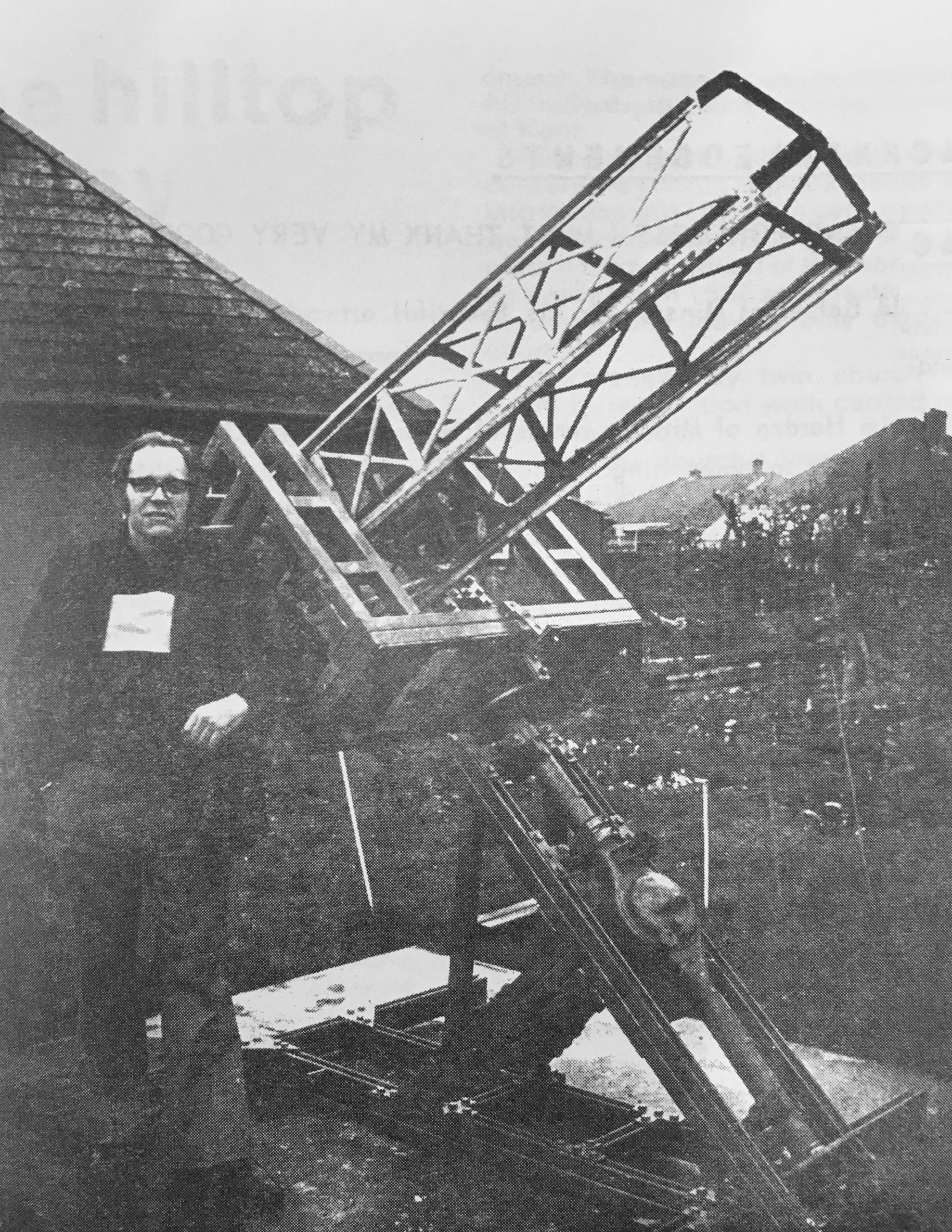

I sought shelter from the rain by visiting some of Sheppey’s many libraries. On the subject of viewing devices, I discovered that a Mr Brian Slade established the world’s first optical workshop for the mentally and physically handicapped in 1970 on the island. They made telescopes from old bed parts, pram wheels rims, disused portholes, motorcycle chains and other scrap metal. Mr Slade also built observatory size telescopes in his back garden and claimed that he had discovered a Sheppey connection to the telescope’s early history. He has also discovered a triple-headed goddess and a fertility well on the island, but that is another story.

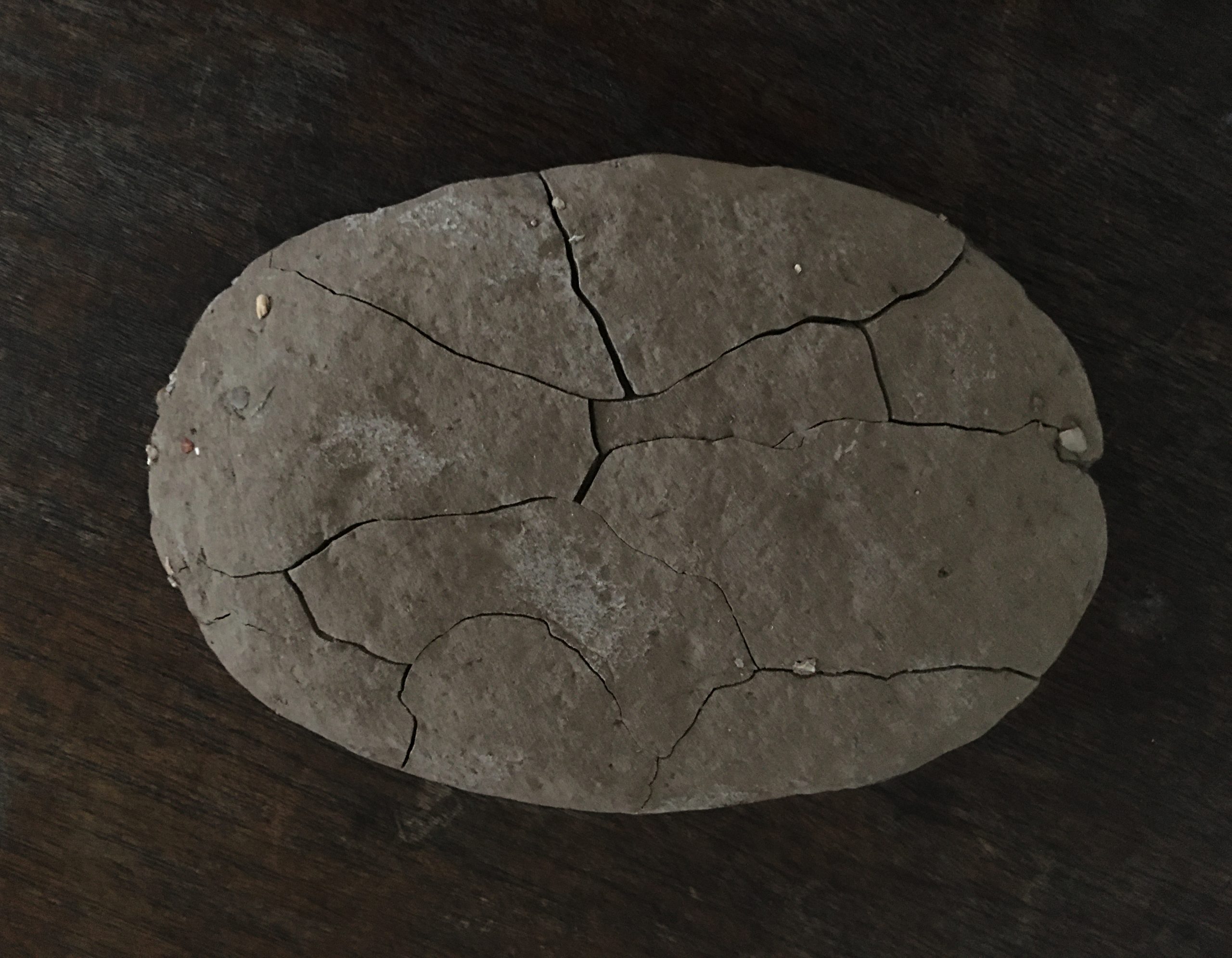

As I imagined the sea drawing itself, I walked to Warden’s point. It is here that you can actually observe the clay cliffs shifting and eroding before your eyes. Within this clay are fossils, relics of a former world where birds had teeth.

In 1827, just before the tidal gauge was erected, an article in ‘The Mirror’ journal stated that the ‘Isle of Sheppey is quickly giving way to the sea and that possibly in a century or two its name may be required to be obliterated from the map’. At Warden’s point a century later, buildings lay on the beach having fallen from the disappearing cliffs. It’s a reminder of our temporality.

Returning a second time to the cliffs after the lockdown. I literally ran down to the beach with excitement and noticed that I observed more, much more. The sea was transforming the fallen clay from the cliffs into egg-like formations perhaps preparing for the birth of a new era.

—

Inspired by her research on Sheppey, Savinder’s newest work Fade, a water-powered slide projector combining concepts from early tidal gauges and rudimentary water clock technology with basic principles of gravity and weight transference, showed at PEER as part of the show Ananas and The Flatfish (November 2020 – February 2021).